MILITARY OPERATIONS

FRANCE AND BELGIUM 1914

![]()

Compiled by Brigadier-General Sir James E. Edmonds

Edited by Macmillan & Co, 1933

![]()

CHAPTER XIII - THE LAST STAGES OF THE RETREAT - 2ND-5TH SEPTEMBER

(Sketches A, 1, 9, 10, 11 & 12 ; Maps 3, 4, 31, 33, 23 & 34)

The Army was growing hardened to continued retirements ; but in the I. Corps, to make the conditions easier for the men, General Haig on the 1st September decided to send off by train from Villers Cotterêts about half of the ammunition carried by his divisional ammunition columns, and to use the fifty wagons thus released to carry kits and exhausted soldiers. This was an extreme measure, taken only after mature deliberation, but it was more than justified by the result.

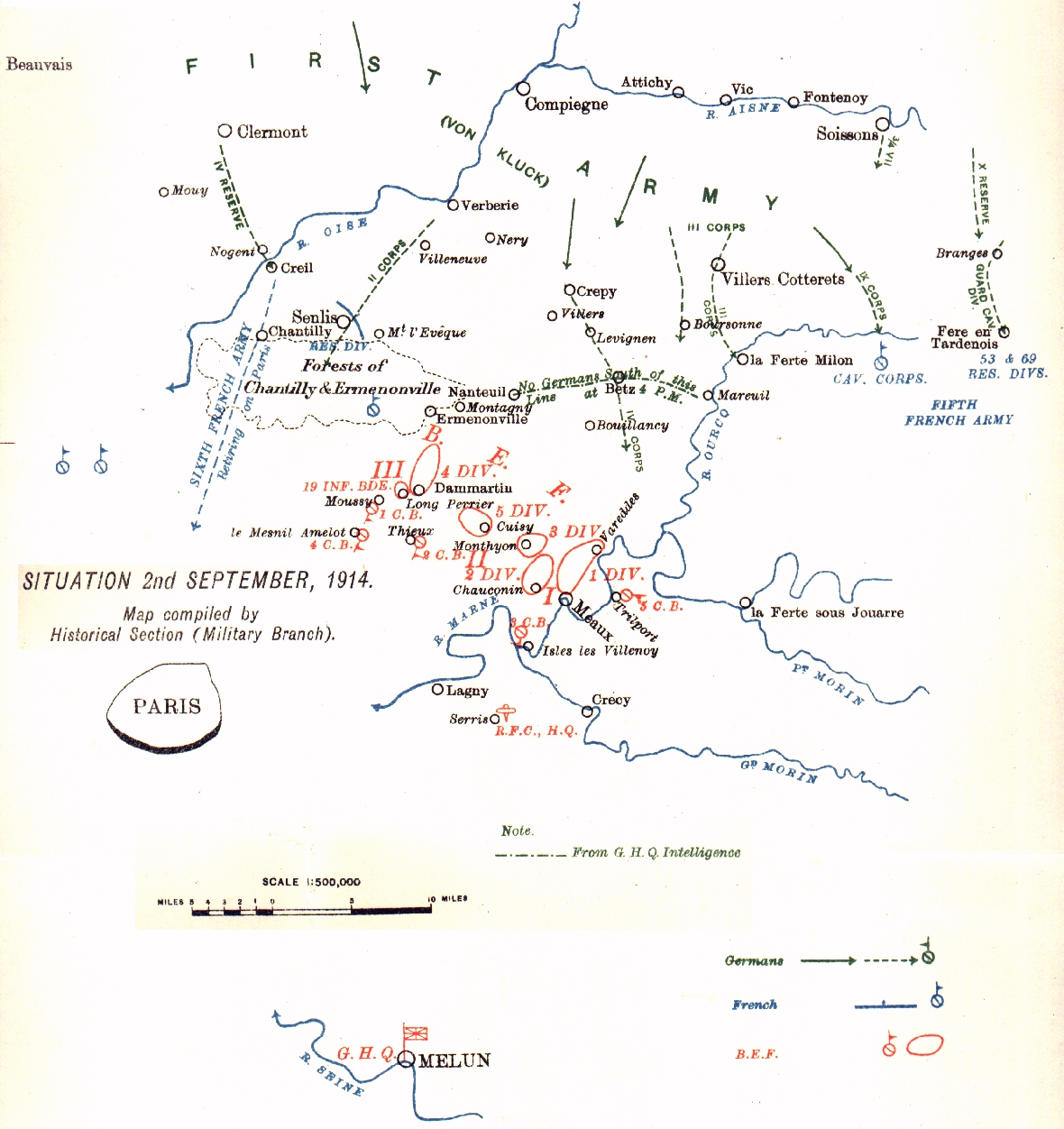

The next day in pursuance of Sir John French's orders, the divisions began moving back between 1 A.M. and 3 A.M. from their billets between La Ferté Milon and Senlis to the line of villages between Meaux and Dammartin, a march of some twelve miles. The I. Corps was on the right or east, the II. Corps in the centre and the III. Corps on the left, with the cavalry on either flank of the force. It was practically unmolested during this move. The 5th Cavalry Brigade, on the eastern flank, heard news of a German squadron moving from Villers Cotterêts upon La Ferté Milon, but saw nothing. The 3rd Cavalry Brigade, on the west of the 5th, had been in motion for fully six hours and was well south of Betz before German shells began to burst over the extreme tail of the rear guard. An hour or so later six or eight German squadrons were seen approaching Bouillancy, the next village south of Betz, but were driven off by the fire of D and E Batteries. The brigade, being no further troubled, then retired slowly to Isles les Villenoy behind the right of the I. Corps, where it arrived late in the evening.

The three brigades of the Cavalry Division on the left a had been disturbed on the night of the lst/2nd September by more than one report that the whole or parts of the German 4th Cavalry Division were moving south through the Forest of Ermenonville behind the British left flank ; and at 2 A.M. the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, on the extreme left, had been ordered to march at once from Mont l'Évêque to clear the defile through the forest for the division. The brigade moved off at 2.30 A.M., taking the road through the forest towards Ermenonville. On debouching from the south-eastern edge it found the road littered with saddles, equipment and clothing. Some enemy force had evidently been in bivouac there and had hastily decamped. Reports came in from inhabitants that two squadrons of Uhlans were at Ermenonville and the next village east of it ; but the British were too late to intercept them. The enemy had withdrawn rapidly, and in the wooded country it was useless to pursue him. Before reaching Ermenonville the brigade came across some motor lorries of the 4th Division Ammunition Column, which had run into a party of German cavalry during the night, and also four abandoned German guns, the marks upon which proved that they were part of the batteries that had been in action at Néry. (The guns were destroyed by gun-cotton charges.) It may be stated here that, except for skirmishes of cavalry patrols, there was no further contact with the enemy during the rest of the retreat.

Though the march of the British force this day was only, a short one, averaging about twelve miles, and the leading units got in early, it was evening before all were in their billets. The heat of the day was intense and suffocating, and made marching so exhausting that several long halts were ordered. In spite of these, there were some cases of heat-stroke.

The march of the I. Corps proved specially trying, since the valley of the Ourcq, for the first half of the way, formed an almost continuous defile. During the passage of this region, the divisions were directed to piquet the high ground as in mountain warfare. The movement presented a fine opportunity to a really active and enterprising enemy, but no such enemy appeared.

An inhabitant of the district has put on record the appearance of the British during this period of the retreat : " The soldiers, phlegmatic and stolid, march without appearing to hurry themselves ; their calm is in striking contrast to the confusion of the refugees. They pass a night in the villages of the Ourcq. It is a pacific invasion . . . as sportsmen who have just returned from a successful raid, our brave English eat with good appetite, drink solidly, and pay royally those who present their bills ; . . and depart at daybreak, silently like ghosts, on the whistle of the officer in charge." (" Les Champs de l'Ourcq, September 1914." By J. Roussel-Lépine.)

The position of the Army at nightfall on the 2nd September was as follows :

|

5th Cavalry Brigade |

} In the villages just north of Meaux. |

|

I. Corps |

|

|

3rd Cavalry Brigade |

Isles les Villenoy, S.S.W. of Meaux. |

|

II. Corps |

In the area Monthyon-Montgé-Villeroy. |

|

III. Corps |

Eve-Dammartin. |

|

Cavalry Division . |

In the area Thieux-Moussy le Vieux-Le Mesnil Amelot. |

Roughly speaking, therefore, its front extended from Meaux north-west to Dammartin. From Dammartin the French Provisional Cavalry Division (Formed temporarily from the fittest units of Sordet's cavalry corps.) prolonged the line to Senlis, from which point north-westward through Creil to Mouy and beyond it lay General Maunoury's Sixth Army, which had been able to withdraw without serious interference by the enemy. On the right of the British the French Fifth Army was still a good march north of them, with the left of its infantry south-west of Fère en Tardenois, some twenty-five miles away ; but General Joffre had issued orders for Conneau's newly formed cavalry corps (8th and 10th Cavalry Divisions and an infantry regiment), which was a few miles nearer, to get in touch with the British next day, and fill the gap between them and the Fifth Army.

The 2nd September had thus passed more or less uneventfully for the troops, but aerial reconnaissance confirmed interesting changes on the side of the enemy, which had been suspected on the previous day. His general march south-eastward seemed for the time to have come to an end, and to have given place to a southerly movement. The general front of Kluck's Army was covered by cavalry from Villers Cotterêts through Crépy en Valois and Villeneuve to Clermont. (The II. Cavalry Corps was, according to Kluck, in line between the IV. and II. Corps, so part of the covering cavalry was divisional.) Behind it from east to west opposite the British were the III., IV. and II. Corps, and there were indications that the heads of the columns were halting to allow the rear to close up, as if apprehensive of danger from the south. The IV. Reserve Corps was to the right rear north-west of Clermont about St. Just, and the IX. Corps was east of Villers Cotterêts, on the same alignment as the cavalry. Up to 4 P.M. no hostile troops of any kind had passed a line, about ten to twelve miles away, drawn from Mareuil (at the junction of the Clignon with the Ourcq) westward through Betz to Nanteuil le Haudouin. In fact, it seemed as though Kluck had not foreseen any such collision with the British as had taken place on the 1st. Possibly he believed them to have moved south-eastward, and such, indeed, had been their direction on the 30th, though on the 3lst it had been changed to south-west to leave more space for the retreat of the French Fifth Army. Moreover, but for the exhaustion which prevented the right and centre of the British Army from reaching the halting-places ordered for the evening of the 3lst, it is probable that there would have been no serious collision at all between the British and the Germans on the 1st September, but that the Germans would have merely brushed against the British rear guards, reported the main body to be still in retreat, and continued their south-easterly march to take the French Fifth Army in flank. Events, however, having s fallen out as they did, Kluck had made one further attempt to cut off the British. Meanwhile on his left Bülow was pressing forward against the French Fifth Army and had, with his main body, reached the line of the Aisne from Pontavert (14 miles north-west of Reims) to Soissons, the head of his advance being on the Vesle. On his front, the Fifth Army had fallen back to the line Reims-Fère en Tardenois.

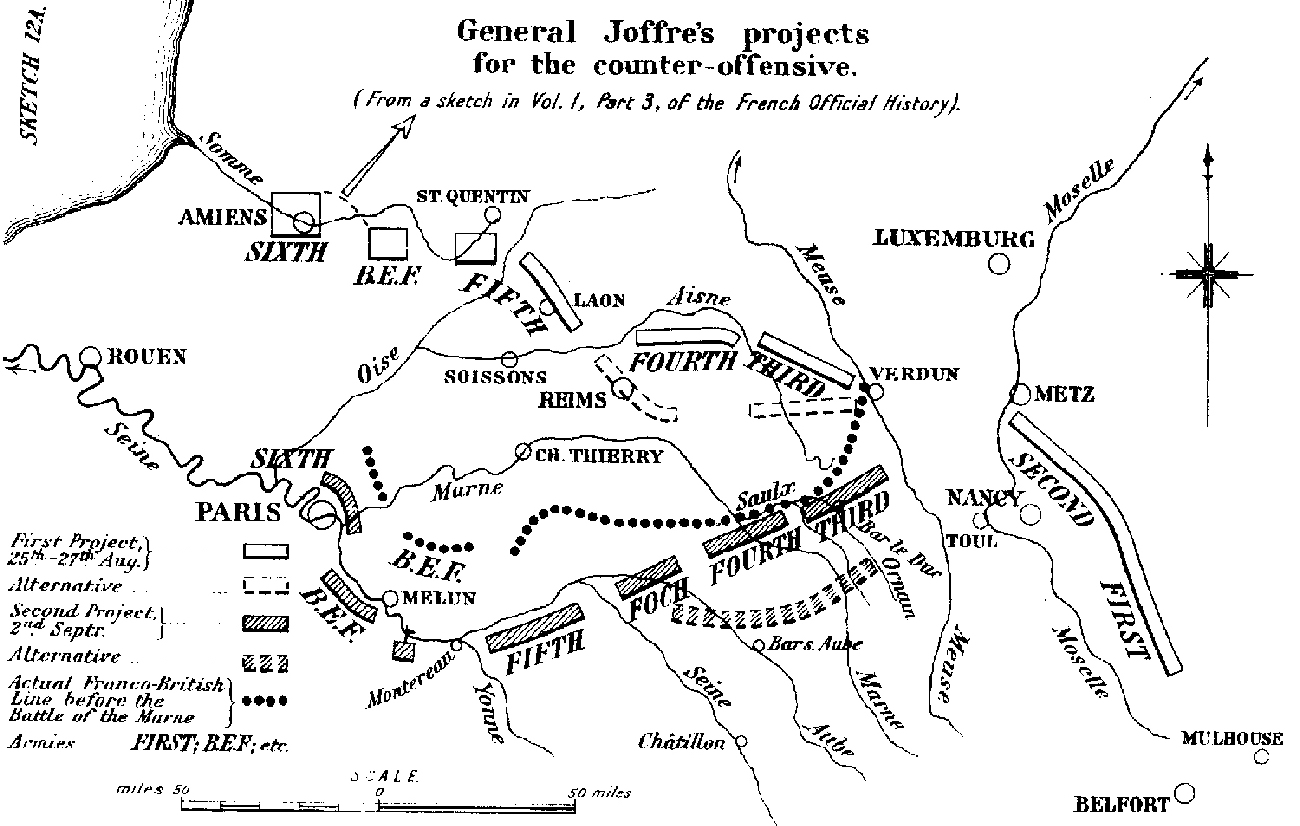

Whilst in Paris on the 1st September, Sir John French made a proposal to the French Minister of War to organise a line of defence on the Marne and there stand the attack of the enemy. This was rejected on the 2nd by General Joffre, mainly, apparently, on account of the position of the Fifth Army, which on that date was close to the Marne with the enemy near at hand. He added : " I consider that the co-operation of the British Army in the defence of Paris is the only co-operation which can give useful results ", and suggested that it " should first hold the line of the Marne, and then retire to the left bank of the Seine, which it should hold from Melun to Juvisy [20 miles below Melun and just outside the perimeter of the entrenched camp of Paris]." Late in the evening, his Instruction Générale No. 4, which forecast a retreat behind the Seine, reached Sir John French. Issued at 2 P.M. on the 1st September, it fixed as the limit of the retirement the line " north of Bar le Duc-behind the Ornain, east of Vitry le François-behind the Aube south of Arcis sur Aube, behind the Seine south of Nogent sur Seine." The Field-Marshal therefore gave orders for the Marne to be crossed on the 3rd, as did General Lanrezac also to his Army, and for the retreat of the British Army to be resumed in a south-easterly direction ; for its continuance in a south-westerly direction would have brought it inside the perimeter of the entrenched camp of Paris, besides tending to increase the gap between its right and the left of the Fifth Army. Since this movement was in the nature of a flank march across the enemy's front, although it turned out that his columns were marching practically parallel to the British, it was necessary to make arrangements to keep the Germans off the high ground on the north bank of the Marne during its execution.

Early in the morning of the 3rd September, therefore, the 5th and 3rd Cavalry Brigades were thrown out to an east and west line north-eastwards of Meaux ; the former, which was supported by a battalion and a battery, covering the loop of the Marne from St. Aulde westwards to Lizy sur Ourcq, and the latter the ground thence westwards to Barcy. German cavalry patrols appeared on the front of the 3rd Cavalry Brigade between 8 and 9 A.M., but did not approach closely, and at 10.30 A.M. the brigade crossed the Marne at Germigny, behind the centre of its sector, and then moving south-eastwards behind its sister brigade, fell into the main road at La Ferté sous Jouarre at noon. The 5th Cavalry Brigade was not troubled until 4 P.M., when a hostile column, which included four batteries, appeared at May en Multien, due north of Lizy on the western bank of the Ourcq. There was some exchange of rifle and artillery fire as Br.-General Chetwode slowly withdrew eastwards, but the Germans were evidently content to see him go, for they did not follow, but took up billets quietly on the western bank of the Ourcq from Lizy northwards. The 5th Cavalry Brigade then crossed the Marne at La Ferté sous Jouarre and reached its billets at 7 P.M., having had no more than five casualties.

Meanwhile, having started between 3 and 4 P.M., the 1st Division had crossed the Marne at Trilport, the 2nd and 3rd at Meaux, the 5th at Isles les Villenoy, the 4th at Lagny and the Cavalry Division at Gournay. Under authority from General Joffre, they or the French blew up all the bridges behind them as they moved south-east, (The first troops of the 4th Division which arrived at Lagny found French engineers about to blow up the bridges there ; only with difficulty was a postponement obtained.) and by evening the B.E.F. was distributed along a line south of the Marne from Jouarre westward to Nogent, I. Corps patrols being again in touch with troops of the French Fifth Army which was also south of the Marne. The Sixth Army, north of the Marne, slightly overlapped the British left.

This march too had proved a trying one ; it was long in point of time as well as distance, for the roads were crowded with vehicles of refugees, and some units were as much as eighteen hours on the road.

During the morning Sir John French learnt from a Note issued by G.Q.G. at 9.30 P.M. on the 2nd, but which did not reach British G.H.Q. and other recipients until the 3rd, that General Joffre had slightly changed his plans from those announced in " Instruction Générale No. 4" He now proposed to establish the whole of his forces on a general line marked by Pont sur Yonne-Nogent sur Seine-Arcis sur Aube-Brienne le Chateau-Joinville, that is to withdraw his flanks further than originally stated, and then pass to the offensive, whilst simultaneously the garrison of Paris acted in the direction of Meaux.

Aerial reconnaissance on this day established the fact that Kluck had resumed his south-eastward movement with rapidity and vigour : the German columns which had been following the British southwards had turned off and were now making their way eastwards and south-eastwards to the passages of the Ourcq. . Unfortunately there are no British air reports after 2.50 P.M. to be found ; but at 5 P.M. G.H.Q. informed General Joffre and General Lanrezac that there did not appear to be any enemy forces left on the British front, and that the whole of the German First Army was about to cross the Marne between Chateau Thierry and La Ferté sous Jouarre to attack the left of the Fifth Army. Between 8.20 and 8.40 P.M. a more detailed message was telephoned by Colonel Huguet, on behalf of G.H.Q., to G.Q.G., the Fifth Army and the Military Governor of Paris : " It results from very reliable reports from British air-men, all of which agree, that the whole of the German First Army except the IV. Reserve Corps [that is to say, " the II., III. and IV. Corps and l8th Division] are moving south-east to cross the Marne between Chateau Thierry and La Ferté sous Jouarre, and attack the left of the Fifth Army. The heads of the columns will without doubt reach the Marne this evening."

At the same time an officer was sent to General Lanrezac's headquarters at Sézanne with a map exactly showing the situation.

The British air reports were confirmed by those of an aviator sent out by the French Sixth Army, who reported, between 7.30 and 8.30 P.M., (The British reports reached the Sixth Army " early in the afternoon " and were confirmed "several hours later." (F.O.A., i. ii.) p. 618.)) the movements of columns (II. Corps) from Senlis south - eastwards on the Sixth Army front, and a very long column (8th Division) moving south-east with its head at 6 P.M. at Etrepilly (close to Lizy on the Ourcq). Nothing could be seen of the I V. Reserve Corps, which had been marked down near Clermont on the previous evening.

Opposite the Fifth Army the German columns were still marching southwards. By 11 A.M. the head of the German IX. Corps had already passed the Marne and had a sharp engagement with the French at Chateau Thierry, 15 miles north-east of the British right. Later another column of this corps crossed at Chézy (below Chateau Thierry), and at 6 P.M. the head of a column (l3th Division) was reported at Mézy (6 miles above Chateau Thierry).

There are no reports, from either French or British sources, of the Germans on the 3rd reaching the Marne between Chézy and La Ferté sous Jouarre (exclusive). The gap there between the French Fifth Army and British does not appear to have been watched except by a party of French cavalry at the bridge of Nogent, which cleared off on the approach of German cyclists. (" Regt. No. 24 " p. 47.) It is now known from German sources that Kluck's divisions, by making marches of 25-28 miles, secured all the bridges in this sector by midnight. (The heads of the divisions of the III. Corps reached the bridges at Nogent, Saulchery, Charly and Nanteuil between 8 and 9 P.M., and established outposts on the heights beyond them. Of the IV. Corps on the night of the 3rd/4th the German Official Account (iii. p. 236) states that it " reached the region of Crouy " ( 10 miles north of Lizy) ; Kluck's map, on the other hand, shows its line established south of the Marne. Neither location is correct. An examination of the histories of the eight infantry regiments of the corps reveals that only one of them, the 66th (7th Division) crossed the Marne on the 3rd. at Saacy, arriving at midnight, and billeting there and in the adjoining village of Citry. All the others in this division marched until midnight in clear moonlight, halting, the 26th at Méry (on the north bank of the Marne opposite Saacy), the 27th and 165th at Dhuisy (6 miles N.N.W. of Saacy). In the 8th Division, the 93rd and 153rd reached St. Aulde (on the Marne N.N.E. of La Ferté) at 2 A.M. and midnight, respectively ; and the 36th and 72nd halted at two small villages, Rouget and Avernes (both 3 miles to the northward of La Ferté) at 2 A.M. and 10 P.M., respectively.) Fortunately one and all arrived too late at the river, for the whole of the French Fifth Army was by that time safely across the Marne, and its left had fallen back after a fight at Chateau Thierry, and was now in line with the British though still separated by a gap of about ten miles.

At 4.35 P.M. the British Commander-in-Chief, certain from the air information that Kluck was moving from west to east and intended no immediate action against him, warned his corps commanders that, unless the situation changed, the troops would remain in their present billets, and would probably have complete rest next day. During the evening, however, Sir John became alarmed by possibilities of the situation should the Germans press into the gap between the B.E.F. and the Fifth Army, and at 11.50 P.M. he issued orders for the remaining bridges over the Marne in the British area to be destroyed and for the Force to be prepared on receipt of a further order to continue its retreat southward. If he fell back it was his intention to bring the whole B.E.F. behind the Grand Morin, and, as a preliminary, to swing back the right or eastern flank. The I. Corps, therefore, was to move first, through Coulommiers, with the 3rd and 5th Cavalry Brigades pushed out to the east, in order to protect its flank and to gain contact with Conneau's cavalry corps, which was reported to be at Rebais, 7 miles away. The II. and III. Corps and Cavalry Division were to stand fast until the I. Corps had reached the Grand Morin, and then fall back in line with it. Every precaution was to be taken to conceal the billets of the troops from aircraft. The movements of the British Army during the past few days had already misled the enemy once and, if its whereabouts could now be hidden, might mislead him again. ( In this, according to Kluck, the II. and III. Corps were successful ; the march and bivouacs of the I. Corps only were observed.)

Accordingly, on the 4th, soon after daybreak, the 5th Cavalry Brigade, with the 3rd in support, advanced east-ward to Doue, midway between the two Morins, and sent patrols forward along both banks of the Petit Morin. At the same time it despatched the Scots Greys to the east towards Rebais there to meet the French cavalry. At 8 A.M. the patrols reported a hostile column of all arms moving south-east along the main road north of the Petit Morin from La Ferté sous Jouarre to Montmirail, but evidently there were parties of the enemy south of the valley, for a troop of the Greys found Germans at Rebais, and had such sharp fighting that only five of its men escaped. At 11.45 A.M. a column of cavalry with guns and three battalions of infantry, evidently a flank guard, were seen moving south-east on the heights between the Montmirail road and the Petit Morin, from Boitron upon Sablonnières ; some of them, crossing the stream, attacked an advanced party of the 5th Cavalry Brigade about a mile east of Doue, but without success. The enemy seems then to have decided that it was time to thrust back this prying English cavalry, and manoeuvred to turn Br. General Chetwode's position from the south ; but when he fell back under cover of the 3rd Cavalry Brigade and the Germans occupied his ground about Doue, they were at once engaged by E Battery, which disabled one of the German guns and did considerable damage among the gun teams. At 6 P.M. Br. General Gough in turn withdrew the 3rd Cavalry Brigade, protected by the fire of the 113th and 114th Batteries, and by the 2nd Brigade, which was in position about Aulnoy. He then crossed the Grand Morin at Coulommiers, and made for Chailly; a little to the south-east.

Meanwhile, by General Haig's orders, the 1st Division had at 4 A.M. been withdrawn into reserve and relieved in the duty of observation over the front from La Ferté to Sammeron (3 miles west of La Ferté) by the 2nd Division. There was some expectation of fighting ; for, although the bridges at Sammeron and St. Jean had been blown up, one of the two bridges at La Ferté sous Jouarre owing to lack of time had not been thoroughly destroyed. (The four bridges had been dealt with by the 23rd and 26th Field Companies R.E. The demolition of the stone-arched bridge at La Ferté was successful ; the second was a six-arched steel girder bridge, and the girders were cut through ; but the ends remained as cantilevers, and the gaps could be crossed by laying a few planks. There was no time to place heavy charges to complete the demolition.). About 8 A.M. indeed a German battalion crossed the river by this bridge, (The German IV. Corps and II. Cavalry Corps crossed at La Ferté sous Jouarre.) but it did not immediately press on, and the 1st Division, pursuing its march methodically, halted at Aulnoy and Coulommiers. During the afternoon Sir John French visited I. Corps headquarters and gave General Haig orders to withdraw, thus for the second time preventing him from fighting. The 2nd Division, which at 4 P.M. began to fall back by brigades in succession to the west of the 1st Division, upon Mouroux and Giremoutiers, was followed only by a few cavalry patrols. The II. and III. Corps and Cavalry Division actually enjoyed a day of rest on the 4th until after dark, when they too moved off south through the night, as will be related. For the moment the Army was concentrated on the Grand Morin.

The information obtained by the Flying Corps on this day was particularly full and complete. The early (6 to 7 A.M.) reports gave the bivouacs of all the corps of the German First Army except the IV. Reserve. The later reports established the continued march, from the front Chateau Thierry-La Ferté sous Jouarre south-eastwards across the Marne towards the left of the French Fifth Army and Conneau's cavalry corps, of the IX., III. and IV. Corps. About 4.30 P.M. two columns of cavalry were seen moving southwards towards the 1st Division at Aulnoy and Coulommiers, and some shelling was observed. (This was the action of the 3rd and 5th Cavalry Brigades.) From the Governor of Paris came information that the II. Corps was moving on Meaux and the IV. Reserve Corps on Betz and Nanteuil. General Franchet d'Espérey, who had taken over command of the Fifth Army from General Lanrezac (For an account of his sudden removal, see his book, " Le Plan de Campagne français et le premier mois de la Guerre " p. 276 et seq.) the previous day, continued the withdrawal of his troops, swinging back his left to meet the German threat against his flank.

It may be noted that on this day the French Ninth Army, under General Foch, came into existence between the Fourth and Fifth Armies. It was organised, merely for convenience of command, from the left of the Fourth Army, and its formation did not, therefore, affect the general situation. (The French Ninth Army came officially into existence as an independent command at 11 P.M. on the 4th September. It had actually been formed on the 29th August as a " Détachement d'Armée." It consisted of the IX. and XI. Corps, 52nd and 60th Reserve Divisions and 9th Cavalry Division from the left of the Fourth Army, and the 42nd Division from the Third Army. Its formation merely reduced the size of the Fourth Army, and put the Fourth and Ninth Armies where the Fourth had been.)

During the afternoon of the 4th September, also, General Galliéni, the recently appointed Military Governor of Paris, under whose direct orders the French Sixth Army had been acting since the 1st September "in the interests of the defence of Paris," came with General Maunoury to British headquarters at Melun. (See " Mémoires du Général Galliéni. Défense de Paris," p. 121, for an account of this visit. For the genesis of the orders for the Battle of the Marne, see Note II. at end of Chapter.) Sir John French was absent, as we have seen, visiting the I. Corps, about whose position he was alarmed, but to his Chief of the General Staff, Lieut.-General Murray, General Galliéni pointed out that advantage ought to be taken at once of the opportunity the German First Army had given by offering its right flank. He added that he had ordered the Army of Paris, as he called his combined forces of the Sixth Army and Paris garrison, to move eastwards that afternoon, and that he proposed, with the concurrence of General Joffre whom he had informed, to attack the German IV. Reserve Corps, which was covering the movement of the First Army. This corps had been reported that morning marching in two columns towards Trilport and Lizy sur Ourcq. Galliéni suggested that the British Army should cease to retreat, and take the offensive next day in co-operation with his forces. In the absence of the British Commander-in-Chief, nothing could be decided, but it was settled provisionally that on the 5th the B.E.F. should change front so as to occupy a general line behind the Grand Morin from Coulommiers westwards (actually Faremoutiers-Tigeaux-Chantéloup), " so as to leave the Sixth Army the " space which was necessary for it." (F.O.A., i. ii.) p. 789). After waiting three hours for Sir John French, but all in vain, at 5 P.M. General Galliéni departed. Whilst this interview between General Galliéni and Lieut.-General Murray with regard to co-operation was taking place at G.H.Q., another was in progress at Fifth Army headquarters between other French and British representatives. On the morning of the 4th General Franchet d'Espèrey had expressed a wish to meet Sir John French, and it had eventually been arranged, as the Commander-in-Chief wished to go to the I. Corps, that the Sub-Chief of the General Staff, Major-General Wilson, with the head of the Intelligence Section, Colonel Mac-donogh, should be at Fifth Army headquarters at Bray sur Seine at 3 P.M. On arrival there these officers found that General Franchet d'Espèrey had a quarter of an hour earlier received a telegram from General Joffre to the effect that it might be of advantage to deliver battle next day or the day after with the Fifth Army, the B.E.F and the mobile forces of Paris, and enquiring whether the Fifth Army was in a fit state to fight. After comparing information as to the movements of the enemy, and discussing the general situation as far as they knew it, General Franchet d'Espèrey after agreement with Major-General Wilson, despatched the following reply to General Joffre :

" I. The battle cannot take place until the day after to-morrow 6th (sixth) September.

II. To-morrow, 5th Sept. the V. (Fifth) Army will continue its retrograde movement to the line Sézanne-Provins [that is facing north-west, with a view to guarding the left flank of the French main Army rather than to an offensive].

The British Army will make a change of direction, so as to face east on the line Coulommiers and southward-Changis [6 miles east of Meaux] provided that its left flank is supported by the Sixth Army, which should advance to the line of the Ourcq to the north of Lizy sur Ourcq [8 miles north-east of Meaux] to-morrow 5th (fifth) September.

III. On the 6th (sixth) the general direction of the British offensive should be Montmirail ; that of the Sixth Army should be Chateau Thierry ; that of the V. (Fifth) Army should be Montmirail."

Thus it was suggested that the Fifth Army should advance northwards, and the B.E.F. and Sixth Army east-wards.

To this message, which was timed 4 P.M., General Franchet d'Espèrey added in his own handwriting :

" The conditions for the success of the operation are :

1. The close and absolute co-operation of the Sixth Army which must debouch on the left bank of the Ourcq to the north-east of Meaux on the morning of the 6th.

It must be up to the Ourcq to-morrow the 5th September.

If not the British won't march.

2. My Army can fight on the 6th, but is not in a brilliant state, the three Reserve divisions cannot be counted on.

In addition, it would be as well that the Detachment Foch should take an energetic part in the action, direction Montmort [11 miles south-west of Epernay]."

With a note of these messages, Major-General Wilson and Colonel Macdonogh returned to G.H.Q.

General Joffre had written to Sir John French earlier in the day confirming his intention to adhere to the plan of retirement already communicated to him. He added :

" In case the German Armies should continue the movement south-south-east, thus moving away from the Seine and Paris , perhaps you will consider, as I do, that your action will be most effective on the right bank of that river between Marne and Seine.

Your left resting on the Marne, supported by the entrenched camp of Paris, will be covered by the mobile garrison of the capital, which will attack eastwards on the left bank of the Marne."

On his return from visiting General Haig, the British Commander-in-Chief, after reading this letter, found that his Chief and Sub-Chief of the General Staff had come to two entirely different arrangements with the Governor of Paris and the Commander of the French Fifth Army : one that the British should be drawn up behind the Grand Morin, facing more or less northward, and the other that it should be north of the Grand Morin, facing east. General Galliéni's communication appeared to be authorised by General Joffre, and to be in agreement with the latter's last letter, whilst Franchet d'Espèrey's plan might land the B.E.F., with its left completely exposed, in the midst of Kluck's Army. (The German II. Corps on the 5th exactly covered the ground Coulommiers-Changis which Generals Franchet d'Espèrey and Wilson had agreed should he the starting line of the B.E.F.) The Field-Marshal was much troubled by what appeared to him to be constant changes of plan ; but there seemed no doubt that the Generalissimo wished the B.E.F. to be withdrawn further to make room for the Army of Paris south of the Marne, (See Sir John French's letter to Earl Kitchener. Appendix 27.) and in view of the gap which existed between the B.E.F. and the Fifth Army, and " because the Germans were exercising some pressure on Haig on this night [4th Sept.]," (Lord French's " 1914"," p. 109.) Sir John French decided to retire " a few miles further south."

At 6.35 P.M., therefore, orders were issued from British G.H.Q. at Melun, for the Army to move south-west on the 5th, pivoting on its left, so that its rear guards would reach, roughly a line drawn east and west through Tournan. The times of starting were left to the corps commanders. The Cavalry Division was further warned to be ready to move from the western to the eastern flank of the Army early on the 6th. A message informing General Galliéni of the movements ordered was sent through the French Mission at British headquarters.

Accordingly before dawn on the 5th, the I. Corps was again on the march southwards with the 3rd Cavalry Brigade as rear guard and the 5th as eastern flank guard. The latter had a skirmish at Chailly early in the morning, but otherwise the march was uneventful, and was indeed compared by the 3rd Cavalry Brigade to a march in peace time. The fighting troops of the III. Corps started at 4 A.M., but the II. Corps moved off several hours earlier, at 10 P.M., in order to avoid the heat of the day. Both corps were unmolested. During the 5th, definite orders for the Cavalry Division to move to the right flank were issued, and in the course of the afternoon it started eastwards across the rear of the Army.

Thus by nightfall, or a little later, the British force had reached its halting-places south-south-east of Paris, and faced somewhat east of north : the I. Corps in and west of Rozoy, the Cavalry Division to its right rear in Mormant and the villages north of it, the II. Corps on the left of the I., in and east of Tournan, and the III. Corps on the left of the II., from Ozoir la Ferrière southwards to Brie Comte Robert, touching the defences of Paris.

The air reports showed during the day the advance of the German First Army across the Grand Morin, and at night the bivouacs of large forces south of that river ; two or three corps (the III., II. Cavalry and IV.) were between the Grand Morin and the Aubetin, and another corps (II.) between them and Crécy. South of a line through Béton Bezoches and west of a meridian through Crécy there were reported to be no Germans ; but the G.H.Q. situation tracing for the 5th September has " fighting at 2.45 P.M." marked on it in a circle around St. Soupplets, so the collision of Maunoury's Army with the German IV. Reserve Corps was known. The left of the French Fifth Army was during the afternoon reported to be around Provins, that is 15 miles to the right rear of the B.E.F.

General Franchet d'Espèrey, before the conference at his headquarters on the 4th, had issued orders for the retirement to the Seine of the French Fifth Army on the 5th and 6th " as quickly as possible and with the least possible losses " ; strong echelons of artillery were to be used in successive positions and the enemy fought by. guns without being given a chance of holding on to the infantry. No modification was made in these orders in consequence of the question asked by General Joffre, as to when the Fifth Army could fight ; so the XVIII. Corps and Reserve divisions marched off at midnight of the 4th/5th, and the other formations of the Fifth Army at 1 A.M.. Thus during the early hours of the 5th both Franchet d'Espèrey and Sir John French wheeled their forces back as if opening the two halves of a double door, increasing the gap between them, and presenting an entry into the Allied line to the enemy.

Meanwhile, during the 5th September, north-east of the capital, General Maunoury's Sixth Army had by General Galliéni's orders advanced north of the Marne towards the Ourcq, and in the afternoon had come into contact with the German IV. Reserve Corps between Meaux and St. Soupplets. This Army was steadily increasing in numbers as divisions reached it from the east. (It consisted on the 5th September of the VII. Corps (l4th and 63rd Reserve Divisions), 45th Division, 55th and 56th Reserve Divisions, the Moroccan Brigade, and Gillet's cavalry brigade-some 70,000 men, with Sordet's cavalry corps attached. Behind it were a group of Territorial brigades under General Mercier-Milon, Ebener's Group of Reserve divisions (6lst and 62nd), and the actual garrison of Paris, four divisions and a brigade of Territorial troops, with a brigade of Fusiliers Marins sent for police duties. The IV. Corps was just arriving, so General Galliéni reckoned he had about 150,000 men available for action as the Army of Paris.) On the right of the British, and slightly to the south of them, General Conneau's cavalry corps (4th, 8th and 10th Cavalry Divisions) was near Provins, on the extreme left of the Fifth Army, which had continued to retire during the 5th, and was now extended north-eastwards from Provins to Sézanne. Thus the gap in the Allied line on this side was some fifteen miles, with four French and British cavalry divisions at hand to fill it.

Opposite the French Fifth Army and the right of the B.E.F., Kluck's Army had continued its south-eastward movement. As aeroplane reconnaissance clearly showed the whole of it (except the IV. Reserve Corps and 4th Cavalry Division, which were observing Paris) had passed the lines of the Ourcq and the Marne and had wheeled to the south, its front stretching along the line of the Grand Morin, which its advanced troops had crossed, from Esternay (near Sézanne) to Crécy (south of Meaux). On Kluck's left, the Second Army was a day's march behind him, its right slightly overlapped by the IX. Corps, so that for a time there was an impression that he had been reinforced. The moment for which General Joffre had waited was come at last. Kluck, in his headlong rush eastwards, had, it appeared, ignored not only the fortress of Paris, but the Sixth Army which, with the British, was now in position, as a glance at the map will show, to fall in strength upon his right flank and rear.

Similarly, further east, parts of the German Fifth Army and the Fourth Army had swept past the western side of Verdun, with which fortress General Sarrail's Third Army, facing almost due west, was still in touch. Thus, whilst the German Sixth and Seventh Armies were held up by the eastern fortresses, the Fifth, Fourth, Third, Second and First Armies had penetrated into a vast bag or " pocket " between the fortresses of Verdun and Paris, the sides of which were held by unbeaten troops, ready to turn on the enemy directly the command should come to do so. Credit has been claimed for General Galliéni that he first discovered the eastward march of Kluck and brought its significance to the notice of General Joffre, and that he immediately took appropriate action with the troops under his command, and prevailed upon the Commander-m-Chief to change his plan for retiring behind the Seine. Be this as it may, the decision to resume the offensive rested with General Joffre.

The retreat of the B.E.F. had continued, with only one halt, for thirteen days over a distance, as the crow flies, of one hundred and thirty-six miles, or, as the men marched, at least two hundred miles, and that after two days' strenuous marching in advance to the Mons canal. The mere statement of the distance gives no measure of the demands made upon the physical and moral endurance of the men, and but little idea of the stoutness with which they had responded to these demands. The misery that all ranks suffered is well summed up in the phrase of an officer : " I would never have believed that men could be so tired and so hungry and yet live." An artillery officer whose brigade marched and fought throughout the retreat with the same infantry brigade has noted in his diary that, on the average, mounted men had three hours', and infantry four hours'rest per day. The late General Sir Stanley Maude, who was on the III. Corps Staff, has put it on record that he did not average three hours'sleep out of the twenty-four ; (Callwell's " Sir Stanley Maude " p. 120.) officers of the lower staffs had less. But all these trials were now behind them : the Retreat from Mons was over.

There have been three other notable retreats in the history of the British Army. All three, that of Sir John Moore to Corunna in the winter of 1808-9, of Sir Arthur Wellesley after the battle of Talavera in 1809, and again from Burgos to Ciudad Rodrigo in 1812, were marred by serious lack of discipline, though the first was redeemed by its results and the success of the final action at Corunna, while the last was reckoned by critics to be the greatest of Wellington's achievements. The Retreat from Mons, on the other hand, was in every way honourable to the Army. The troops suffered under every disadvantage. The number of reservists in the ranks was on an average over one-half of the full strength, and owing to the force of circumstances the units were hurried away to the area of concentration before all ranks could resume acquaintance with their officers and comrades, and re-learn their business as soldiers. Arrived there, they were hastened forward by forced marches to battle, confronted with greatly superior numbers of the most renowned army in Europe, and condemned at the very outset to undergo the severest ordeal which can be imposed upon an army. They were short of food and sleep when they began their retreat, they continued it, always short of food and sleep, for thirteen days ; and at the end of the retreat they were still an army, and a formidable army. They were never demoralised, for they rightly judged that they had never been beaten.

The B.E.F., forming as it did only a very small portion of the line of the French Armies commanded by General Joffre, had no independent strategical rôle in the opening phases of the war. When the Germans turned the Allied left by an unexpectedly wide movement through Belgium, the Generalissimo decided that his only chance of stopping them was " by abandoning ground and mounting a new operation " ; (Rapport du Général Joffre au Ministre de la Guerre, 25th Aug. 1914.) to this Sir John French had naturally to conform. The operation, which involved the assembly of a new Army in the west to outflank the enemy, required time to prepare. General Joffre at first hoped, whilst his First and Second Armies held Lorraine, to be able to stand on the line Verdun-river Aisne (Vouziers-Berry au Bac)-Craonne-Laon-La Fère-Ham, and thence along the Somme. This line he intended to entrench. (Directive of 25th August, 10 P.M.) The Germans, however, pressed on too closely to permit it, and widened their turning movement. There was no alternative to fighting at a strategical and tactical disadvantage but a further general retirement, " hanging on as long as possible, avoiding any decisive action," but giving the enemy severe lessons as opportunities occurred. (General Joffre's letter to G.H.Q. of 30th August.)

Instead of being beaten piecemeal by superior forces as in 1870, the French, after the initial failure of their offensive, withdrew in good time. Such fights as took place, and there were many all along the front besides Guise, (Beaufort, La Marfée, Murtin, Tremblois, Chilly, I.aunais, besides the Battles of Signy l'Abbaye and Rethel.) resulted not in a Woerth or a Spicheren, but in the Allies slipping away after inflicting severe losses on the enemy. ( General Graf Stürgkh, head of the Austrian Mission at German G.H.Q., gives the heavy losses suffered by the Germans in the preliminary engagements as one of the principal reasons for the defeat at the Marne (" Im Deutschen Grossen Hauptquartier," p. 88). The extent of these losses has not yet been revealed.) In such operations, the B.E.F., at Mons and Le Cateau and in smaller actions, was eminently successful : it had no difficulty in more than holding its own whenever contact occurred, hitting hard and then marching off unmolested. Only those who have commanded British troops are able to conceive what they can accomplish.

By some it has been thought that the B.E.F. could have done more ; in particular it might have assisted the French at Guise.

It has been shown in the narrative that one of the reasons that General Joffre ordered General Lanrezac to take the offensive was to relieve the pressure on the British, and Sir John French might at least have allowed the I. Corps to assist. On the other hand, in his dangerous position on the outer flank of the Allied Armies for many days, he had not only to bear in mind General Joffre's general instructions to avoid decisive action and the necessity of husbanding his force for the coming battle when the Armies should turn, but to recall that he commanded nearly all the available trained staff officers, officers and men of the British Empire, the nucleus on which the New Armies were to be trained and initiated in war ; above all, he had to remember the instructions of the Government, that " the greatest care must be exercised towards a minimum of losses and wastage."On the 5th September there were some twenty thousand men absent of the original numbers of the B.E.F. ; but, as in all great retreats, a fair proportion of these rejoined later ; the official returns show a figure of a little over fifteen thousand killed, wounded and missing. The loss of war material is difficult to set down exactly. Some transport was abandoned, as is inevitable at such times ; many of the valises and greatcoats were discarded or burnt and a very large proportion of the entrenching tools left behind. As to guns, forty-two fell into the enemy's hands as the result of active combat, and two or three more through one mishap or another, were left behind. Such a casualty list can, in the circumstances, be only considered as astonishingly light. Its seriousness lay in the fact that, whether in guns or men, the loss had fallen almost wholly upon the left wing.: the II. and III. Corps, and above all upon the II. Corps, which had borne the brunt of the fighting.

It was impossible to expect that the deficiencies in men and material could be immediately made good. Practically all units received their first reinforcements, the " ten per cent reinforcements ", on the 4th and 5th September, and these, added to the replacement of the Munsters in the 1st (Guards) Brigade by the Cameron Highlanders (hitherto Army troops), brought the I. Corps more or less up to strength. But the far graver losses of the II. Corps, especially in guns and vehicles, could not be so quickly repaired. The rapid advance of the Germans to the west had made the bases at Boulogne and Havre unsafe, and had actually dispossessed the British of their advanced base at Amiens. The advisability of a change of base was foreseen by the Q.M.G., Major-General Sir William Robertson, as early as the 24th August, and from that date all further movement of men or stores to Havre or Boulogne was stopped. By the 27th, Boulogne had been cleared of stores and closed as a port of disembarkation ; and on the 29th St. Nazaire on the Loire was selected as the new base. (The L. of C. ran from St. Nazaire by two railway routes, one via Saumur and the other by Le Mans, to Villeneuve St. Georges just south-east of Paris, whence there was one route to a varying railhead.) At that time there were sixty thousand tons of stores at Havre ; also fifteen thousand men and fifteen hundred horses, besides eight hundred tons of hay at Rouen, all awaiting transfer to St. Nazaire. By the 30th of August the Inspector-General of Communications, Major-General F. S. Robb, had telegraphed his requirements in tonnage to Southampton ; and on the 1st September the transports for the troops were ordered to Havre. By the 3rd September all stores had been cleared from Rouen, and all troops from Havre ; and by the 5th every pound of stores had been removed from Havre. In fact, in these four days twenty thousand officers and men, seven thousand horses and sixty thousand tons of stores had been shipped from Havre to St. Nazaire, a considerable feat of organisation.

A mere comparison of dates, however, will show that, despite this great effort, some days were bound to elapse before the gigantic mass of stores could be landed, the new base thoroughly organised, and all arrangements working smoothly for the despatch of what was needed to the front by a longer line of communication. The arrival of the first reinforcements on the 4th and 5th September was only secured by most strenuous exertions. It was obvious that the II. Corps must enter upon the new operations with its ranks still much depleted, and lacking one-third of its divisional artillery.

THE GENESIS OF THE BATTLE OF THE MARNE SEQUENCE OF EVENTS ON THE 4TH SEPTEMBER l914

At 9 A.M. General Galliéni, in order to be prepared to take advantage of the march of the German First Army south-eastwards past Paris, issued a warning order to General Maunoury (Sixth Army) :

" It is my intention to send your Army forward against their [the German] flank, that is in an eastward direction, in liaison with the British troops.

I will indicate your direction of march as soon as I know that of the British Army. But take measures at once, so that this afternoon your troops will be ready to march, and to-morrow can begin a general movement east of the entrenched camp of Paris.

Send cavalry reconnaissances immediately into the sector between the Chantilly road [which runs northward from Paris] and the Marne." (Mémoires du Général Galliéni," p. 114 ; General Clergérie's (Galliéni's Chief of the Staff) "Le rôle du Gouvernement de Paris du 1 ` au 12 septembre 1914," p. 75.)

This plan was telephoned to G.Q.G. about 11 A.M. (possibly as early as 10 A.M.), with the suggestion that " an order should be issued from G.Q.G. that the Army of Paris should get on the march in the evening, towards the east, this Army being able to operate, according to circumstances, either north or south of the Marne."

General Galliéni subsequently set out to visit British G.H.Q. as related in the text.

On his return he found the following cipher telegram from the Commander-in-Chief (sent off at 12.20 P.M., received in Paris 2.50 P.M.) :

" Of the two proposals which you have made to me relative to the employment of the troops of General Maunoury, I consider the more advantageous one is to send the Sixth Army on the left [south] bank of the Marne, south of Lagny.

Please arrange with the Field-Marshal Commanding-in-Chief of the British Army for the execution of the movement." (F.O.A., i. (ii.), Annexe No. 2326, where it is stated that this answer is in the records, but not the telephone message which occasioned it.) Immediately after the despatch of this message General Joffre telegraphed to the commander of the Fifth Army :

" Circumstances are such that it might be advantageous to deliver battle to-morrow or the day after to-morrow with all the forces of the Fifth Army, in co-operation with the British Army and the mobile forces of Paris, against German First and Second Armies.

Please inform me if you consider that your Army is in a state to do so with any chance of success. Reply at once." (Idem No. 2327. He also asked the same question of General Foch, who replied at once that he would be ready to take part in the battle proposed for the 6th.")

What happened at G.Q.G. at Bar sur Aube has been related at length by Commandant Muller, General Joffre's officier d'ordonnance. (" Joffre et la Marne," pp. 81 et seq.) The Operations Staff was divided in opinion, some of the officers being in favour of allowing the Germans to penetrate further into the space between Verdun and Paris before striking ; the others advocated seizing the opportunity, " essentially fleeting," which had presented itself. The Commander-in-Chief had not yet made up his mind. " The heat was stiffing. Seated in the shade of a large weeping ash, in the yard of the school of Bar sur Aube, or astride a straw-bottomed chair, in front of his maps hung on the wall, he turned over in his mind the arguments for and against. Silently, as the afternoon passed, his decision ripened. . . He came to the idea of extending the local action proposed for the Paris garrison to all the Allied forces of the left wing. Towards 6 P.M., without waiting for the information he had requested, he ordered the draft of an Instruction in this sense to be prepared."

During dinner the answer from General Franchet d'Espèrey arrived, which stated that the battle could not take place before the 6th, and towards 8 P.M., as General Joffre was making himself acquainted with it, he was called to the telephone by the Governor of Paris with reference to the telegram he had received in which General Joffre had stated that it would be more advantageous to use the Sixth Army south of the Marne.

" General Galliéni reported to General Joffre that the Sixth Army had made arrangements to attack north of the Marne (right bank) " and it appeared to him to be impossible to modify the general direction to which the Army was already committed, and he insisted that the attack should be launched without any change in the conditions of time and place already laid down. Very quickly, the General-in-Chief accepted the suggestion, which, for that matter, fitted in with the combined operation of which he had already admitted the eventuality, and on which, at this moment, considering himself sufficiently enlightened, he irrevocably decided."

General Joffre gave his decision to General Galliéni on the telephone, and the latter was thus able to issue his definite order to the Army of Paris at 8.30 P.M. on the 4th for its movement eastwards on the north bank of the Marne, so as to be abreast of Meaux on the morning of the 6th, ready to attack in liaison with the British.

For the B.E.F. and the other French Armies orders had to be prepared, enciphered and despatched, and this, as will be seen in the next chapter, took many hours, so that none of the commanders, except Galliéni, received instructions for the battle until the morning of the 5th.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()